The Multi-Union

Backfire from a famous Brooklands racer

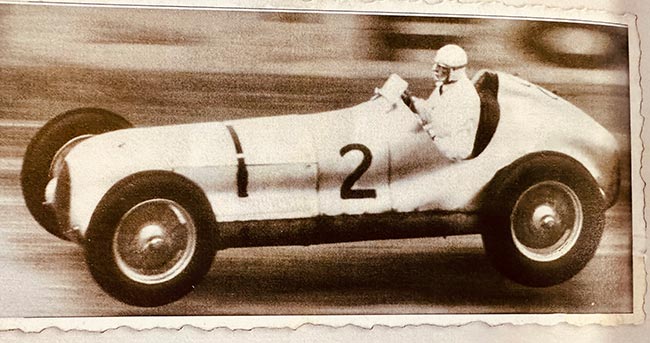

Above: Chris Staniland behind the wheel of the magnificent Multi-Union. The car is airborne at the notorious bump at Brooklands Outer Circuit.

The air was cold and musty as we made our way into the hidden, cave-like storage area bordering the little workshop in Wales. When I held up a torch to peer inside, the light glinted off many silvery surfaces.

This ‘tomb’ would soon reveal the most secretive automotive re-discovery of the early 2000s, It would also answer one of the most frequently asked questions in the inner circle of Brooklands enthusiasts: was the Multi-Union still alive?

As we rolled the dusty remains of the great Multi-Union out into the light, the answer was both yes, and no.

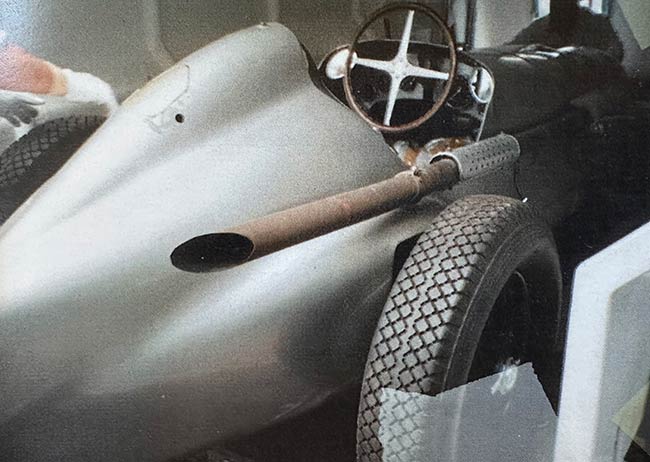

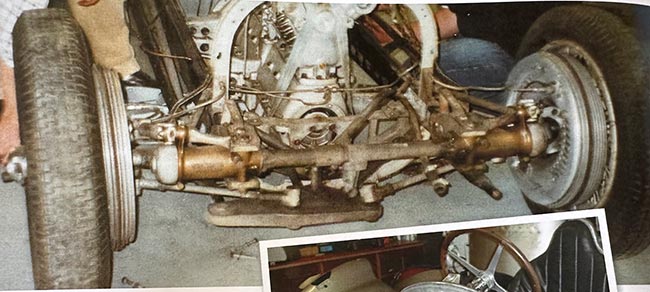

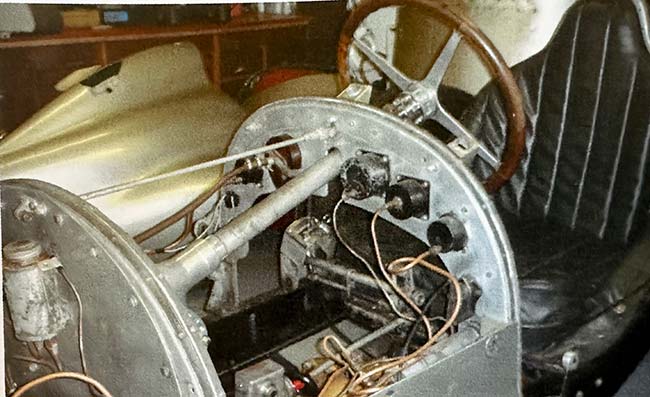

Above: The remaining parts of the Multi-Union as re-discovered in 2005.

For so many years it had been standing there, partially disassembled and hidden from all bar those who’d put it there.

Together with the owner, we planned to put everything back together to see how much of the original, once-glorious machine remained.

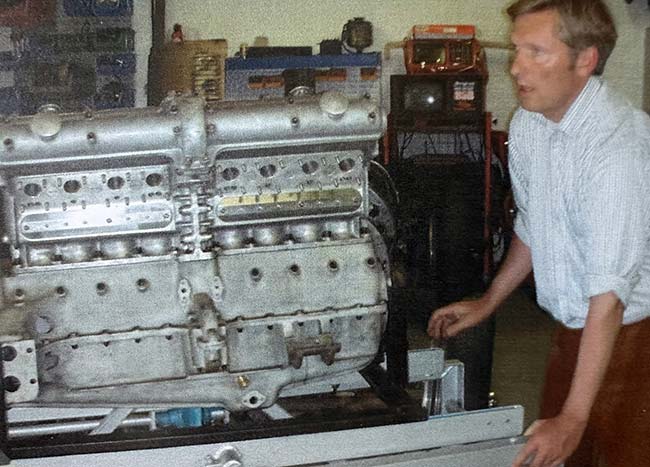

Above: Michael Kliebenstein pushing the non-original Alfa Romeo 2900 B engine out of hibernation.

Above: All reassembled, Michael tries out the cockpit for size.

The Multi-Union began life as an Alfa Romeo Tipo B P3. More specifically, it was the ex-Scuderia Ferrari narrow-bodied Alfa Romeo Tipo B (2900 B) Monoposto, chassis 5003, SF 37.

It was bought and campaigned by Raymond Sommer until just after the 1935 Donnington Grand Prix. Sommer had qualified third in the Tipo B but retired just beyond the race’s halfway point. Presumably that disappointment facilitated the sale of the car to British racer Chris Staniland..

Christopher Stainbank Staniland was a fearless racer who began his career on fast motorcycles – mostly Velocette, Norton and Excelsior-JAP – before buying the old Tipo B P3 from Sommer. In 1932 he drove Malcolm Campbell’s 38/250hp Mercedes-Benz SS in the JCC Brooklands 1,000-mile race, gaining a lot of experience despite failing to finish. As an aside, the numberplate of that car was GP10 which today belongs to Markus Kern.

During the week, Staniland was chief test pilot with Fairey Aviation Company. Tragically, he died on 26 June 1942, aged 36, when the Fairey Firefly prototype aircraft he was flying broke up over Sindlesham, near Wokingham.

Back in the late-1930s however, the increasingly uncompetitive old Alfa Romeo P3 was dismantled and redeveloped in two stages for Brooklands racing. After the first round of modifications in 1938, Staniland drove the newly-christened Multi-Union to a Brooklands Outer Circuit Class D lap record of 141.45mph.

Additional modifications were made for 1939, including an even more Mercedes-Benz W25-like body. In its final specification, Multi-Union II would very likely have taken Cobb’s outright record, if not for an engine fault and the no-small matter of war breaking out.

Today, the Multi-Union remains the second quickest car, after the 24-litre Napier-Railton, to have lapped the Brooklands circuit.

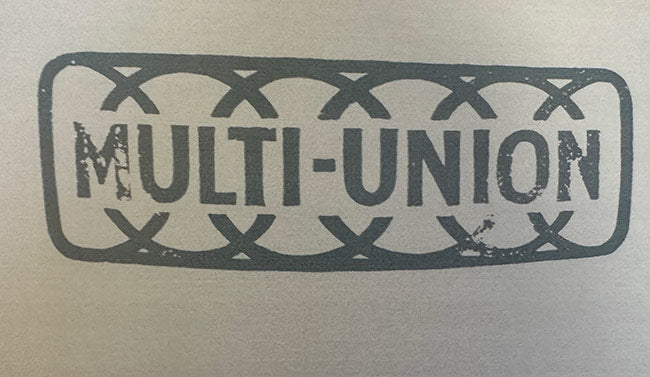

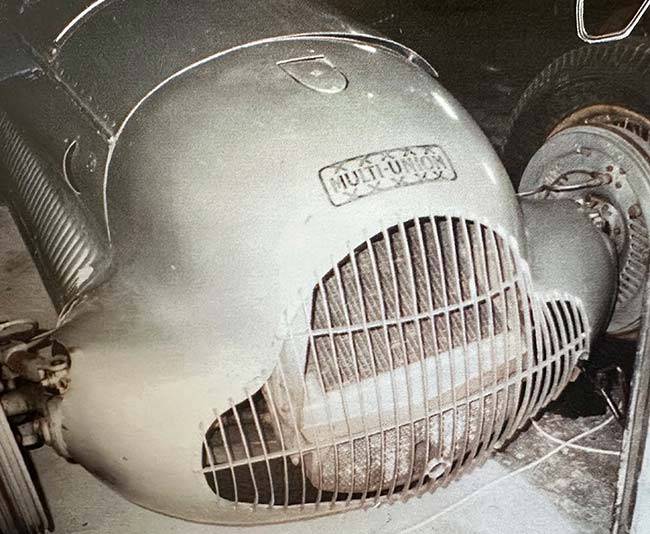

The Multi-Union incorporated many aircraft-inspired technical innovations. In 1937 W.C. Devereux of aircraft parts supplier High Duty Alloys and Lockheed Brake Company backed Staniland, both financially and with technical know-how. Further knowledge and support came from famous racer and engine developer J.S. Worters – a multi-talented team, hence the Multi-Union name and logo.

Above: The interlocking rings logo was meant to honour the team effort of W.C. Devereux of High Duty Alloys, Lockheed Brakes, J.S. Worters and Chris Staniland. Nothing to do with Auto Union.

Above: The interlocking rings logo was meant to honour the team effort of W.C. Devereux of High Duty Alloys, Lockheed Brakes, J.S. Worters and Chris Staniland. Nothing to do with Auto Union.

Driven by the belief that there was enough capacity left in the old Vittorio Jano design for further development, Worters fitted two new airplane-sourced superchargers, enlarged the ‘blower’ ports, fitted a longer induction manifold, replaced the two Weber carburettors with two large, specially developed Solex units and enlarged the engine’s bore, increasing the capacity to almost three litres. The compression ratio was raised considerably and new water ports were manufactured in the cylinder head for better valve cooling. Special pistons and connecting rods were made and a new four-speed gearbox with an improved, long-geared differential was engineered.

Above: Sophisticated Tecnauto front-axle with its large trailing links has survived, as have the specially developed oversized Lockheed brakes.

The drivetrain changes were necessitated by the fragility of the Alfa’s novel dual-propshaft system. During all of its earlier races at Brooklands, the threat of transmission trouble was never far away.

Above: The front grille looks very original. Large parts of the bespoke body remain.

Bore and stroke were 68.5 x 100mm, giving a swept volume of 2,947cc. Maximum engine revolutions were 6,200rpm (some say 6,500rpm, but I have my doubts about that), up from the standard car’s 5,500rpm red line.

The chassis was worked on in several stages. It received a Tecnauto independent front suspension utilising extra large trailing links and coil springs in torsion while at the back the rear axle was given two coil springs on each side with location by a Panhard rod. Suspension and steering were modified too.

Very large aircraft-style hydraulic Lockheed brakes were fitted while specialists Serks fabricated a sophisticated V-shaped, oversized radiator. The oil tank was moved from the tail to the nearside of the cockpit. The fuel tank was altered to fit flush under the rear cowling. There was an additional oil cooler in the front, beneath the complex radiator.

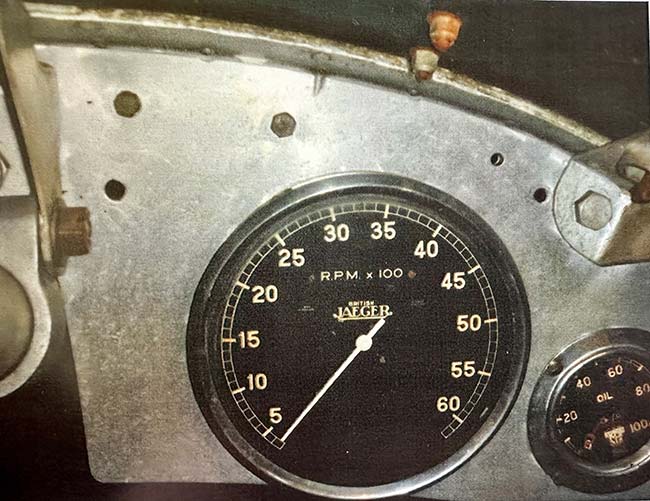

Above: Most of the gauges seem to be sourced from aircraft. The boost gauge looks positively Spitfire to me. Smiths oil temperature gauge alongside.

Above: Jaeger rev counter marked up to 6,200rpm.

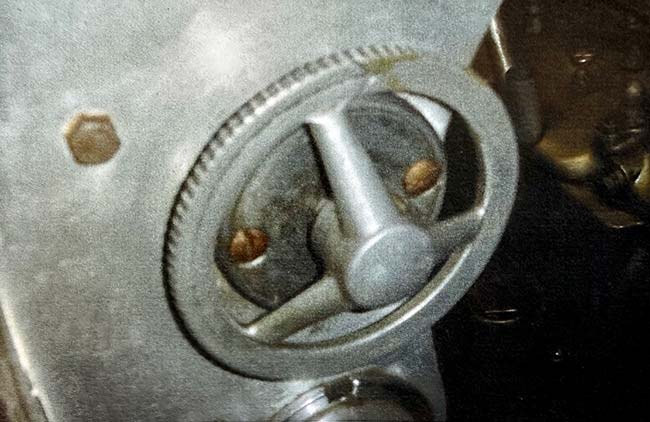

Above: Ingenious Lockheed brake tap allowed manual adjustment of brake ratio.

In the cockpit, we found an aluminium tap for manually varying the brake ratio from 50/50 to 75/25 front/rear. There must have been Bowden cables somewhere to control the Armstrong dampers, but they were long gone. The instruments appeared to have been sourced from aircraft apart from the rev counter which is by Jaeger and is marked up to 6,200rpm.

When reading accounts written by Bill Boddy, John Bolster, Doug Nye and Denis Jenkinson about the road racing history of the Multi-Union, I found out that it won at Phoenix Park in 1938. But its most tremendous performances were all on the outer circuit of Brooklands. At the August Bank Holiday meeting in 1939, an attempt was made on the average lap speed record of 143.44mph set by John Cobb’s 24-litre Napier-Railton. Unfortunately chronic misfiring set in on the Multi-Union. Possibly due to stretched inlet valves or an ignition problem. The car did a lap averaging 142.30mph while running (reportedly) on only seven cylinders.

In practice, it did 160mph over the flying quarter, and firing on all eight cylinders of the beautiful double-overhead camshaft engine, it would undoubtedly have broken the lap record. The fuel used was nitro-benzine.

John Bolster said the Multi-Union was a great car worthy of its great driver. And Denis Jenkinson has said that it was a better Alfa P3 than Alfa Romeo made.

So what became of the Multi-Union?

Doug Nye calls what happened to the car in the 1980s an ‘appalling act of vandalism’. I couldn’t agree more. But I found out that it could have been much worse.

Without naming names, a known collector decided to remove all the original P3 parts from the Multi-Union in order to take chassis 5003 back into a Tipo B P3.

Above: Revived P3 chassis 5003 in its original narrow-bodied Scuderia Ferrari form. Robert Fink sitting in the car, ready to leave the Monaco parc fermé. Michael Kliebenstein, wearing the headphones.

The motivation behind stripping the car and trying to recreate ‘the original’ Tipo B isn’t worth getting into other than to mention that, for sure, an original P3 was more valuable in those days. Today though, I wouldn’t be so sure about that.

Luckily, and this is where the outcome could have been worse as, at least, the parts specific to the Multi-Union were not destroyed in the process. Instead, the remaining parts (plus some new engine and suspension parts) were eventually put together on a new chassis.

Above: The Multi-Union was a sleek machine. Disguising its Alfa Romeo origins very well. Replacement engine and chassis notwithstanding, today it is very much complete on its wheels.

On the day we re-discovered the car after it had seemingly vanished for 26 years, I had a good look and can largely say that the remaining original parts are: most of the body (not the scuttle), the cockpit with its instruments, the gear lever, the brake tap, the Tecnauto front axle, the Solex carburettors, fuel tank, oil tank, radiator, seat cushions, steering wheel, wheels and hubs and the very unusual Lockheed brakes.

I felt there was clearly real empathy to this project, a genuine attempt to preserve as much of the Multi-Union as possible. Of course none of these parts were in any way compatible with any other original P3, which is probably why they have survived.

Above: The scuttle, as found in the Multi-Union, looks fairly new.

Above: The non-original Multi-Union engine with the original huge Solex carbs. The compressors and manifolds look larger than those found in a standard P3, but I wouldn‘t go so far as to say they are original to the Multi-Union. Does anyone know?

Above: The original 3-litre Multi-Union engine back in P3 configuration with small carbs and compressors. Large parts of the body were replaced. The scuttle might be original to the Multi-Union.

The parts with questionable originality include the two blowers, the manifolds, gearbox, transmission and rear axle. These need to be dismantled to assess them in detail. But the unique carbs are original to the Multi-Union. That’s obvious. I admired the beautifully made Solex float chambers many times on that day.

On the whole though, the reassembled Multi-Union looked very much complete on its wheels, in nearly the same form as it was in its Brooklands heyday. Of course with new chassis and engine, but still. Maybe one day it might even be drivable in this form, who knows.

Meanwhile, over the last decades, the original chassis 5003 with its Multi-Union 3-litre engine has been very active in P3 form. Robert Fink, who owned the car for a period of time, described it as immensely powerful, driving long, fast corners in uninterrupted four-wheel drifts, tyres alight with white smoke.

I once saw Robert coming out of the Monaco tunnel in a full four-wheel drift. He told me afterwards that he started the drift exiting Portier and never lifted after that. That’s how powerful the Multi-Union engine was.

Above: Robert Fink in chassis 5003 at slippery Loews hairpin during the Monaco Historic Grand Prix. He described the car as ‘immensely powerful’ and always ready to spin its wheels, even at high speeds in fourth gear.

Looking back, it took years of effort to gain access to the remains of the record car, but it was well worth it. Out of respect for the owner at the time, it is only now that I reveal, for the very first time, the photos I took then.

Today, the situation around the Multi-Union is complicated. Without going into too much detail, I can only hope that soon we will all be able to see her running again, under her own power. I have heard that such plans are in motion.

To end my little story, I would like to quote from John Bateman’s book, The Enthusiasts Guide to Vintage Specials:

‘If we had a Ministry of Motor Racing looking after our heritage the Multi-Union would have been mounted on a plinth in a museum long ago, as a superb example of British enterprise and craftmanship of the immediate pre-1939 period, and as a memorial to Flt. Lt. C.S. Staniland, one of the test pilots who helped to make the Royal Air Force the strong military arm that it was’.

Anorak fact:

After the war the Multi-Union was owned by the Fry cousins and then by G.F. Yates, who blew up the engine at Brighton speed trials in 1949. It was rebuilt by the great Louis Giron in his garage near Brooklands.

The original Multi-Union turned up for its final outing in its original form some time in the 1980s – I think with Chris Mann driving at the VSCC. That was that.

4 comments

At one point, during the 1970sI believe, the Multi Union belonged to Patrick Lindsay, who entered it at Silverstone in the April 1972 VSCC meeting. The Donington Collection seems to have displayed it at some stage. I recall it reappearing during the 1980s, but it seems very sad that such a unique car was allowed to be dismantled.

Jonathan Blackwell

It is always a pleasure to read Michael Kliebenstein’s narrative history on little known vehicles, just seems to uncover the un-known. Great article.

Keith Riddington

What wonderful news that so much of this amazing and important machine is extant. I do hope that it can be fully documented and finally reinstated and then, perhaps Porter Press can publish a ‘mega’ book on it.

Very excited to see this.

Many Thanks

Andrew

Andrew King

I heard that the owner has both the Multi Union and the fake Tipo B which came out of it. I hope he is brave (and rich enough!) to reverse the vandalism. There are plenty of original Tipo Bs around. I would much rather see the “proper” Multi Union running. Such a unique and special car. I am sure with proper set up it would run very well. The Tecnauto IFS has been shown to work very effectively on ERA R2A and many Maseratis. And the big events such as Goodwood accept modern built cars now anyway, so I am sure they would accept both cars which may come out of this, maybe in the same race!

Steven Lines

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.